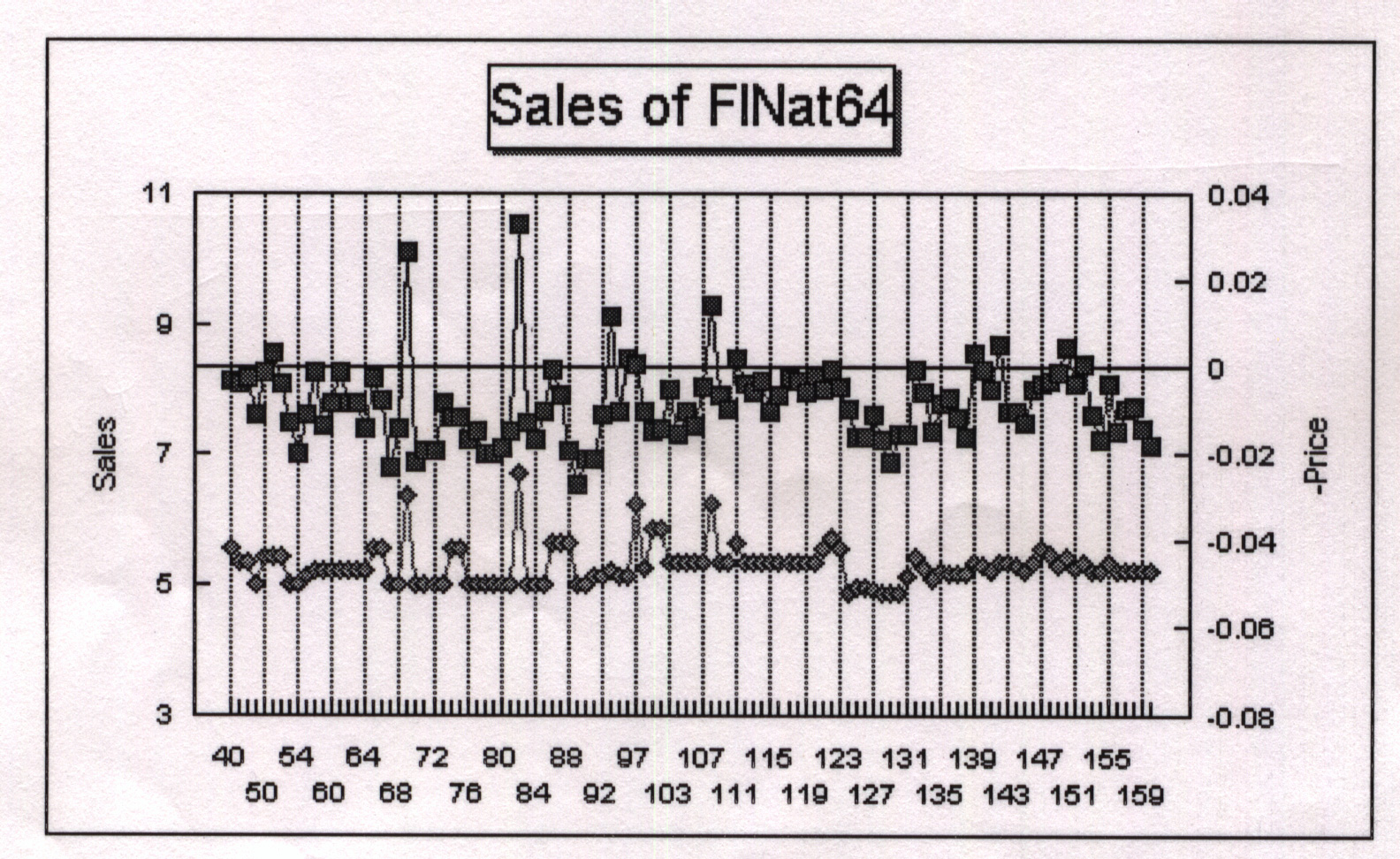

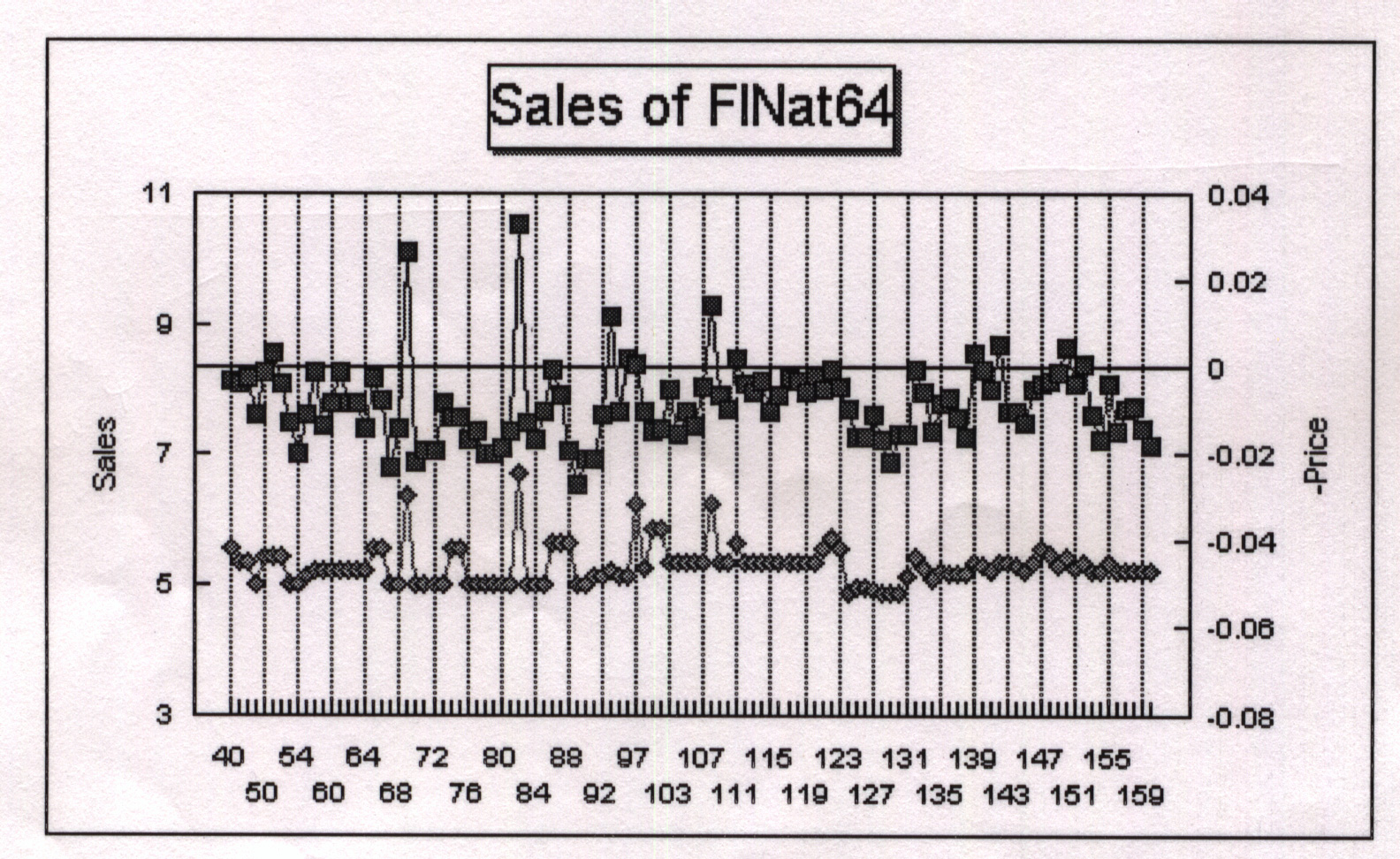

Figure 1

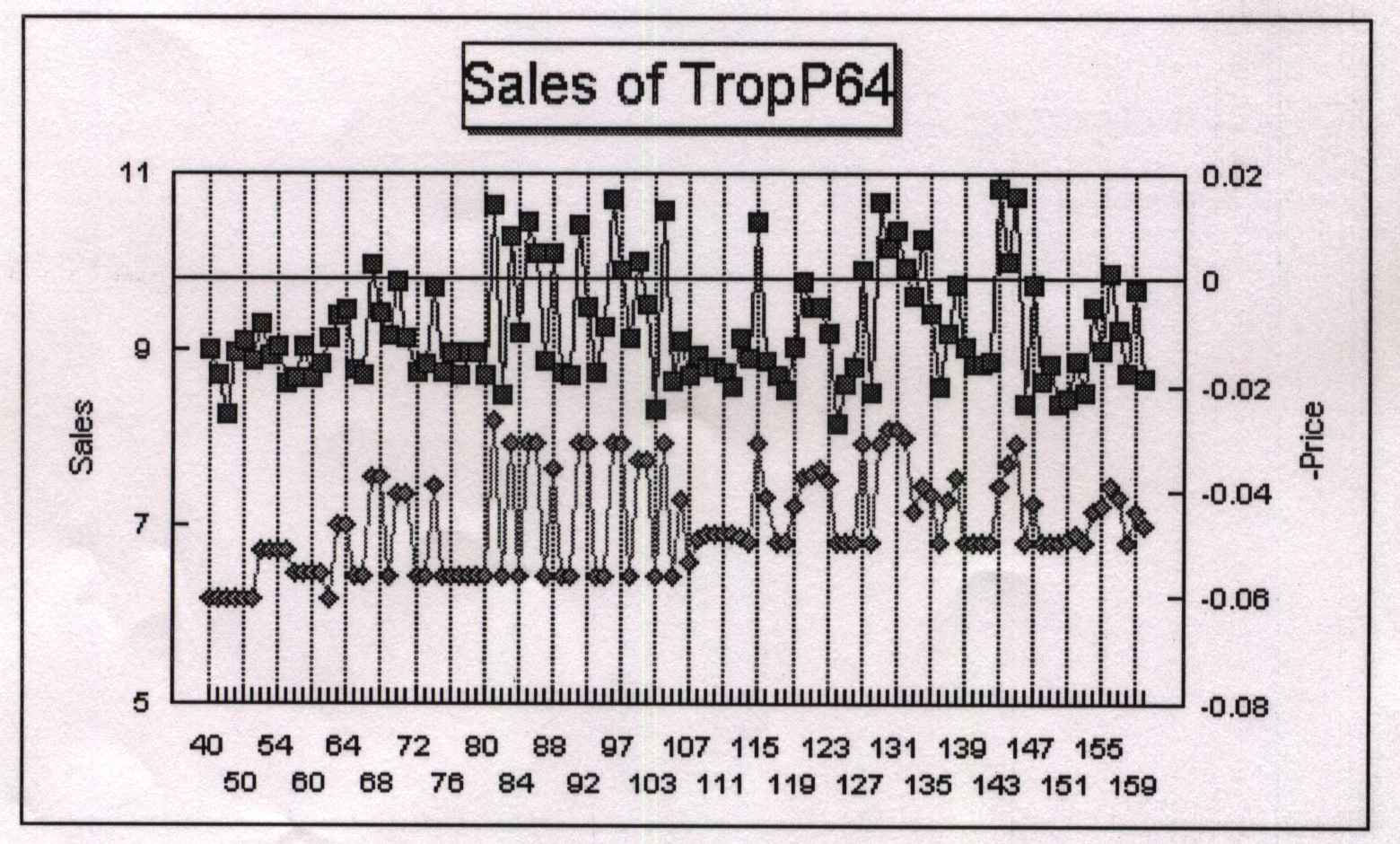

Figure 2

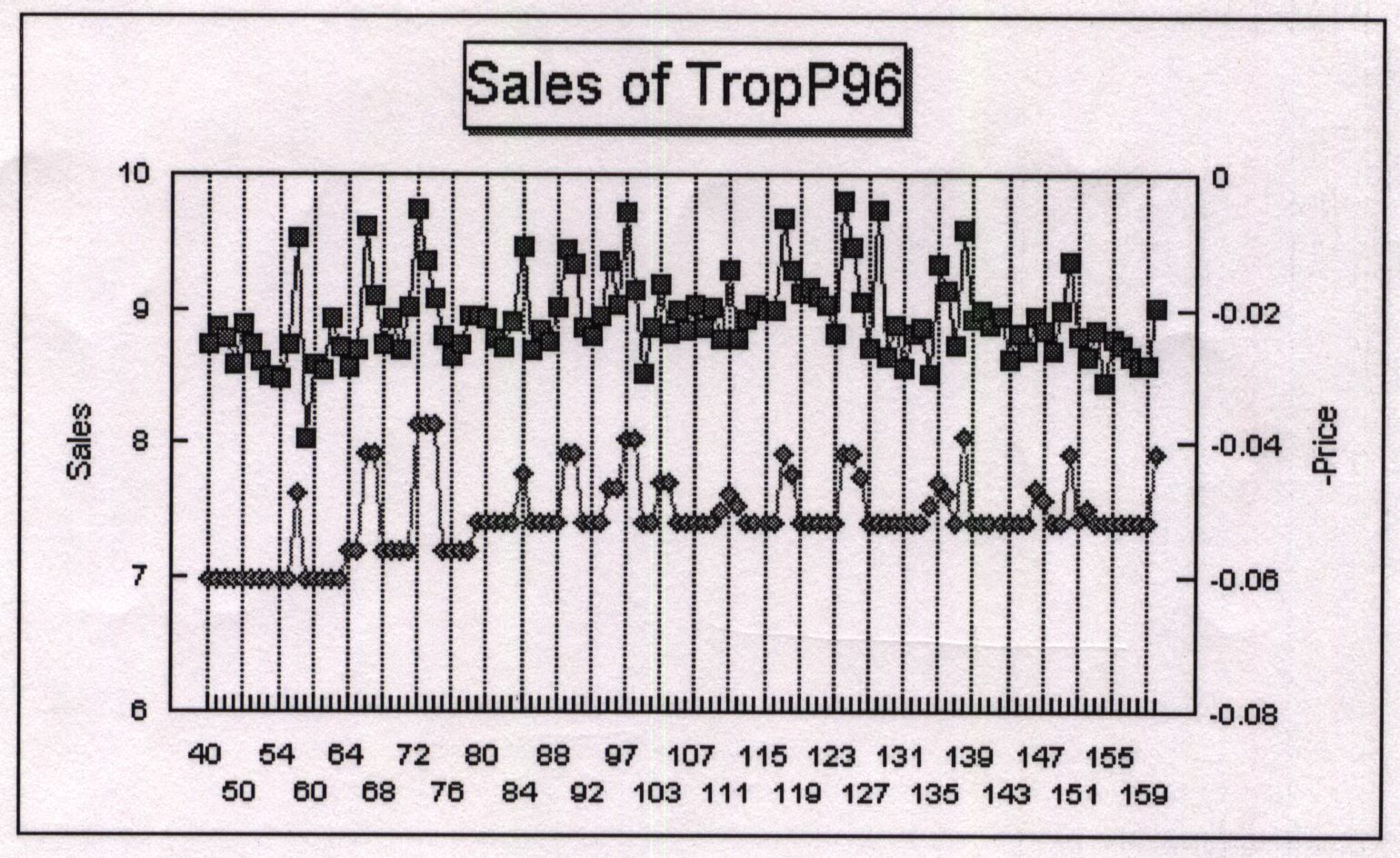

Figure 3

Aside from developing a methodology of wide potential use, this paper applies the technique to micro-marketing, a problem of great interest to marketers in general, and more specifically to chain retailers. One of the fundamental principles in marketing is the design of policies tailored to the needs of particular consumer segments. This paper shows how a retail chain can customize its pricing policies to the characteristics of each market area.

I was impressed by the way Alan structured the micro-marketing problem. The idea of constraining the pricing strategy to constant revenues was quite clever, because it avoids the problem of substitution with other product categories. However, I wonder whether profit maximization is the main goal in setting the pricing policy for frozen orange juice. First we need to ask ourselves why retailers use price promotions for this product category. Product categories with short purchase cycles such as frozen juices are good candidates for attracting shoppers to the store, because they are likely to be purchased every week, and because shoppers are more likely to notice the ``deal-value'' of the promotion.

Integrating the profit estimation within the Gibbs sampler was also quite smart; because of the non-linearity of the profit function, the mean profit is likely to be different from the profit at mean prices. I wonder whether one could not also incorporate the gradient search for optimum prices into the simulations, to produce posterior densities of the optimum prices and profits.

Overall, the conclusions from this particular application of the model are that frozen orange juices have been under-priced, and that prices should be increased towards a greater gap among the price tiers.

These conclusions were based on an optimization of the ``everyday'' prices for each brand in each store. In other words, the focus in this analysis has been on the long-term effects of the everyday price level on sales. The main question in my mind is whether this long-term strategy might be based on short-term responses to price-promotions observed in the past. I see the changes in ``everyday'' prices as shifts in the average price level for each brand over time, while it is possible that, in the past, consumers have been responding to weekly fluctuations in prices due to price-promotions. This might become more clear with my next question.

A few weeks before this symposium, Alan was kind to offer his data for my perusal. At the time, I wished he weren't so kind, because I now had to do something with the data. Pressed for time, I decided to at least plot the sales and prices for one of the stores. I must admit this ``data analysis'' pales in comparison to the sophisticated modeling presented during this symposium. Nevertheless, I learned something interesting, which I will share with you.

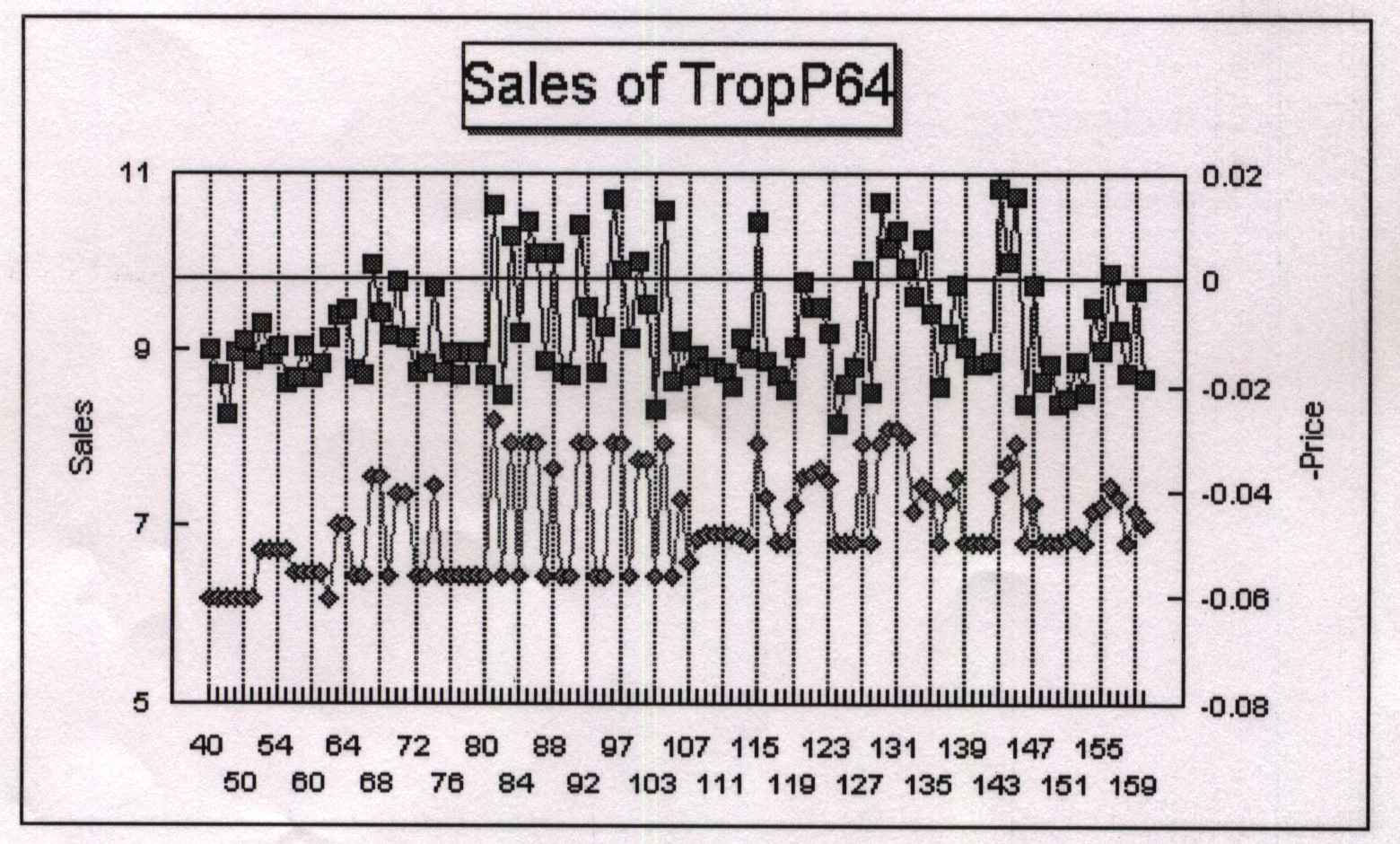

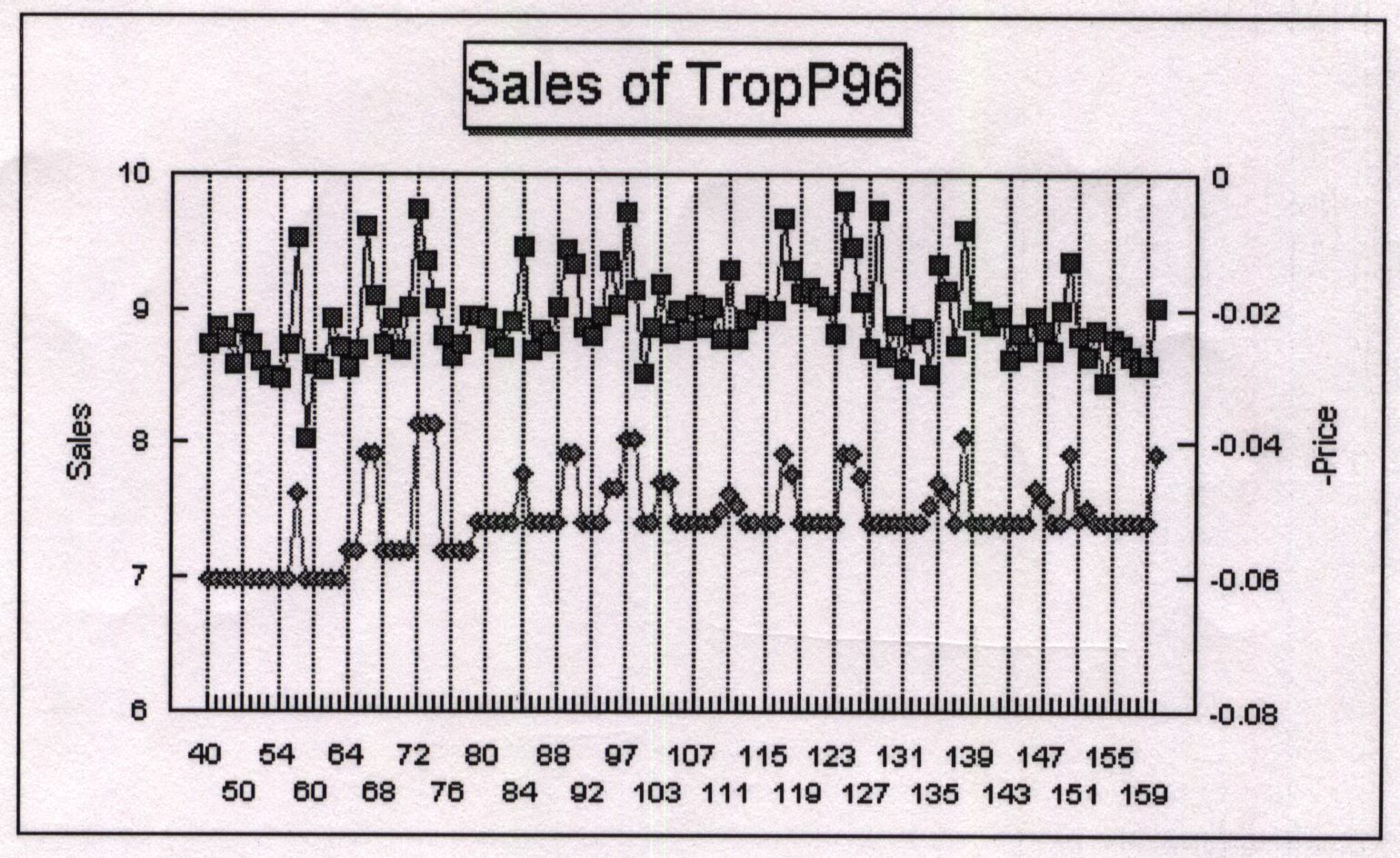

The charts below show the ``plots of sales and prices'' (with inverted signs) for three brands at the first store in the database; prices are represented by diamonds, and sales by squares. I noticed two interesting patterns in all three charts. First, the ``everyday'' price is fairly smooth over time, with noticeable ``bumps'' (in the negative price curve) caused by price promotions of very short duration (a couple of weeks). Second, it seems clear from these charts that most of the variance in sales that can be explained by price is caused by the brand's promotion. It is also reasonable to expect that another portion of sales variance would be explained by the sudden promotions of competing brands.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Of course my charts for three out of 12 brands in one of the 83 stores do not prove anything. At the very most, they bring to mind a potential problem that can be handled by separating the promotional discount from the everyday price, leading to two sets of elasticities. Promotional elasticities could be used to determine the optimal price-promotion strategy, while the everyday price elasticities would lead to the micro-marketing policies discussed in this paper. However, because most of the variance in prices within a brand/store seem to be due to the short-term discounts, if the same pattern occurs in other stores, I would expect much smaller and less accurate everyday price elasticities than the ones reported in the manuscript.

While in principle it would be optimal to define a pricing strategy for each brand in each store, considering that the typical supermarket carries more than 30,000 items, one can see that such a micro-marketing strategy could create a management nightmare. A more practical solution is the one considered at the end of Alan's paper, where he classifies stores into elasticity zones. In other words, managers might find it more feasible to establish pricing policies for classes of stores, defined on the basis of their similarity in cross-elasticity structures. This idea brings back to mind my earlier comment that another potential solution to the estimation problem could be a finite-mixtures model that would estimate the demand systems within each latent-class of stores.

Go to written version of paper

Go to written version of paper