Bio Sketch

General

Robert E. (Rob) Kass is the Maurice Falk University Professor of Statistics and Computational Neuroscience in the Department of Statistics & Data Science, the Machine Learning Department, and the Neuroscience Institute at Carnegie Mellon University. He received a B.A. in Mathematics from Antioch College, a Ph.D. in Statistics from the University of Chicago, and was a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton University before joining Carnegie Mellon in 1981.Kass's early work was on Bayesian inference, and on differential geometry in statistics; since 2000 his interest has focused on statistical methods in neuroscience. These different endeavors have been united by the goal of understanding how reasoning from data produces reliable scientific knowledge. In the case of Bayesian inference, Kass and colleagues provided comprehensive re-assessment of two of the most fundamental issues, evaluation of evidence concerning hypotheses and determination of prior probabilities, both of which relied on new methods and re-formulations developed by many people. In neuroscience, Kass has concentrated mainly on analysis of data representing the primary mode of communication among neurons, known as spike trains, which are described well by mathematical models called point processes. His work has developed, investigated, and illustrated the utility of tractable data-analytic statistical models within the point process framework. Physiological application domains have included vision, audition, memory, movement, and brain-computer interfaces. The most recent work has focused on identifying interactions across two or more parts of the brain during behavioral tasks. Kass is co-author of the book Analysis of Neural Data, and has many overview articles that highlight the often-subtle ways statistical reasoning can advance science.

At Carnegie Mellon, Kass was Department Head of Statistics for 9 years and Interim Director of the precursor to the Neuroscience Institute for 3 years. He served as Chair of the Statistics Section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, founding Editor-in-Chief of the journal Bayesian Analysis, and Executive Editor (editor-in-chief) of the international review journal Statistical Science. He received the Outstanding Statistical Application Award from the American Statistical Association and what is now called the Distinguished Achievement Award and Lectureship from the Committee of Presidents of Statistical Societies. He is an elected Fellow of the American Statistical Association, the Institute of Mathematical Statistics, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and an elected member of the National Academy of Sciences.

Additional Details

Robert E. (Rob) Kass received his Ph.D. in Statistics from the University of Chicago in 1980. His early work formed the basis for his book Geometrical Foundations of Asymptotic Inference, co-authored with Paul Vos. His subsequent research has been in Bayesian inference and, beginning in 2000, in the application of statistics to neuroscience. Kass is known not only for his methodological contributions, but also for major review articles: the first on geometrical methods ( Statistical Science,1989), was followed by two on fundamental issues in Bayesian statistics, one with Adrian Raftery on Bayes factors (Journal of American Statistical Association, 1995) one with Larry Wasserman on prior distributions (Journal of American Statistical Association, 1996); then there was a pair with Emery Brown on statistics in neuroscience (Nature Neuroscience, 2004, also with Partha Mitra; Journal of Neurophysiology, 2005, also with Valerie Ventura), and, with 24 others, an overview of computational neuroscience emphasizing essential mathematical and statistical ideas (Annual Reviews of Statistics and its Applications, 2018). The final review (Journal of Neurophysiology , 2023), with 4 trainees, summarizes methods for identifying interactions across brain areas. His book Analysis of Neural Data, with Emery Brown and Uri Eden, was published in 2014.

With various co-authors, Kass has also written on statistics education and the use of statistics, including the short article Ten Simple Rules for Effective Statistical Practice, which received more than 100,000 views during the first 10 weeks after it was published. In 1991 he began the series of eight international workshops Case Studies in Bayesian Statistics, which were held every two years at Carnegie Mellon, and was co-editor of the six proceedings volumes that were published by Springer. He also founded and co-organized the eight international workshops Statistical Analysis of Neuronal Data, from 2002 to 2017. The ninth iteration (with new organizers) took place in the Spring of 2019.

Kass has served as Chair of the Section for Bayesian Statistical

Science of the American Statistical Association, Chair of the

Statistics Section of the American Association for the Advancement of

Science, founding Editor-in-Chief of the journal

Bayesian Analysis, and Executive Editor (editor-in-chief) of the international review journal Statistical Science.

He is an elected Fellow of the American

Statistical Association, the Institute of Mathematical Statistics, and

the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He has been

recognized by the Institute for Scientific Information as one of the

10 most highly cited researchers, 1995-2005, in the category of

mathematics (ranked #4). In 2013 he received the Outstanding Statistical

Application Award from the American Statistical Association for his

2011 paper in the Annals of Applied Statistics with Ryan Kelly

and Wei-Liem Loh.

In 2017 Kass received what is now called the Distinguished Achievement Award and Lectureship from the Committee of Presidents of Statistical Societies (prior to 2020 "Disinguished Achievement" was instead "R.A. Fisher"). The lecture may be found here (starting at 25:15 in the video)

and a shorter version, edited to remove most of the technical material, may be found here with the corresponding CMU press release summary here.

A 2017 interview of Kass in Statistical Science (published in 2019) may be found here.

In 2023 he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences.

Kass has been been on the

faculty of the Department of Statistics at Carnegie Mellon since 1981; he joined the Center

for the Neural Basis of Cognition (CNBC, run jointly by CMU and the University of Pittsburgh) in 1997,

and the Machine Learning

Department (in the School of Computer Science) in 2007.

He served as Department Head of Statistics from 1995 to 2004 and Interim Co-Director of the CNBC (CMU-side director) 2015-2018.

He became the Maurice Falk Professor of Statistics and Computational Neuroscience in 2016

(see announcement here and the text of his acceptance speech is below) and became University Professor in 2024. Kass has served on several academic advisory committees and from 2018 to 2022 was on the Governing Board of the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre for Neural Circuits and Behavior in London.

Kass has provided a brief summary of his interests in 5 sentences and 4 questions.

Some additional detail on Kass's research may be obtained from his

NIH bio.

More than 80% of Kass's neuroscience publications have involved spike trains. That work is summarized here. His views on the relationship between statistics and machine learning were articled in this 2021 commentary, which appeared in Observational Studies.

Videos on many subjects, often relatively short, can be found here.

Interviews

- A Conversation with Robert E. Kass, interviewed by Sam Behseta for Statistical Science journal, Vol. 34, Number 2 (2019), pp 334-348.

- Other interviews

- 2018 online interview

- 2016 radio interview (12 minutes)

Image of My Life

For people like me, such scribbles seem to capture the deepest part of human existence: symbolic thought, made explicit.

My early lab work

In the spring of 1972 (my second year in college) I worked in the Department de Pathologie at the University of Geneva, Switzerland. There I learned a variety of lab techniques (I had previously worked in a different lab, doing various jobs, at Harvard Medical School), including tissue culture and time-lapse photographic microscopy.

The director of the lab, Guido Majno (a close personal friend of my father's), had become interested in the phenomenon that wounds heal much more slowly when circular than when straight, or rectangular. He called this the "turtle" effect because he imagined a circle of turtles walking toward each other and getting stuck when their shells collided, leaving a circular gap (analagous to slow healing).

I decided to run an experiment on this by growing fibroblasts in culture, and creating small wounds in the cultured layer, then creating a movie of them as they grew in. (I did this surreptitiously, after hours, because I knew I would not have been given permission to do this on my own.) The results were astonishing: in time-lapse we could see the cells slowly moving toward each other, then one would "extend an arm" (cytoplasm) toward another, they would wrap each other and pull, and then suddenly hundreds of cells would pile on top of each other. In other words, we could see mechanistic aspects of wound healing in vitro. My report on the turtle experiments may be found here. Guido raised his eyebrow when I told him about what I had done (right at the end of my stay in his lab), but when he watched the movie he also thought it was amazing. He promised to follow up, repeat, and publish the results. This never happened. My impression is that this was about the time that people were starting to work out mechanisms of fibroblast locomotion (e.g., Theriot, JA and Mitchison, TJ (1992) J. Cell Biol., 118: 367-377, and refs therein).

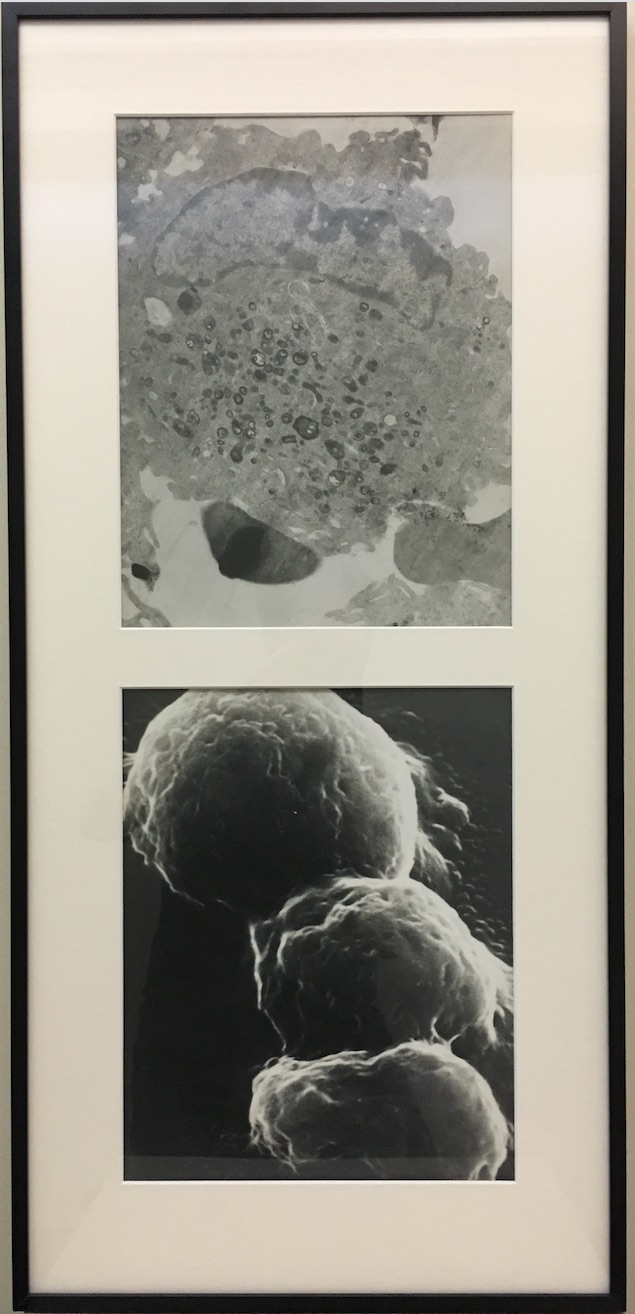

In my earlier jobs (especially in high school and just after) I had learned electron microscopy. I saved an electron micrograph of an

alveolar macrophage, because I had done all the work, from harvesting the cells from the animal, to embedding the tissue in epoxy,

to slicing with a diamond knife, to running the microscope, and finally developing and printing the picture. It is the top one here:

Text of my speech accepting the Maurice Falk chair in 2016

Thank you Farnam. Thank you Richard and Chris, for your remarks and for making this chair happen, thank you to all of the staff who have been involved with the logistics for this event, particularly Joanne Ursenback in Richard’s office and, of course also my CNBC assistant Barb Dorney. Thank you everyone.

I’m sorry my good friend and statistics-in-neuroscience co-conspirator Emery Brown couldn’t be here due to a family emergency, but I did speak with him this morning and I’m glad he was able to email Chris his speech.

My heartfelt thanks go especially to the others who’ve come in from out of town, Constantine Gatsonis: I hesitate to call you my “oldest” friend in statistics, but let’s just say we go a long way back. And my siblings, Jim, Nancy, Peter. It means so much that you could be here.

I was originally very much looking forward to thanking a series of people, explicitly, who have been crucial to my career here, in Statistics, in Machine Learning, and in the CNBC. However, as soon as I started writing down names I realized the list was way too long, and it just wouldn’t be practical. So even though I’m deeply indebted to so many of you for all you’ve done for me, I’m not going to acknowledge anyone by name; except, there is one person who went above and beyond anything I could have possibly expected, consistently providing insight when I needed it, and wise advice when I sought it, my wife Loreta: thank you Lorie. And, looking back over the past 35 years nothing fills me with more pride than my two sons, who have become such fine young men; so thank you Nico and Gabe for the pleasure I get whenever I think of you.

Most of you are not intimately familiar with the bestowing of endowed chairs at Carnegie Mellon, and while we make a big fuss, so it’s clearly a great honor, you may wonder what they mean, concretely, for the recipient. Several people have asked me this.

In practice, as far as I can tell, it boils down to three things.

First, and probably most importantly, having observed carefully many colleagues over the years I can say for sure that holding this chair will definitely have a profound impact, on my letterhead; and as Mari Alice McShane, Heidi Sestrich, and Carl Skipper will verify, if it’s one thing I care about it’s the appearance of my letterhead; because, these days, the audience for our letters is almost exclusively made up of people who don’t already know us, so I figure a slightly more positive initial impression may, at least in some cases, alter perception, adding a pinch of gravitas to the letter’s content. I’m grateful for that.

Then there’s a discretionary fund. It’s small, but very much appreciated. For example, in airports I prefer to answer email on my laptop, and I’m happy to report that I no longer feel it’s just too extravagant to pay for Boingo; that is a great relief.

Finally, a surprising part of this whole process involved an email, with two attachments, which I received shortly after I officially started holding this chair on July 1. The first attachment was a short note of recognition from the Provost; the second was a longer document, from Donor Relations, in the office of University Advancement, that is, folks who interact with donors to help raise money for things like endowed chairs. This second document listed across 2 full pages, all the duties to be performed by me on their behalf, and at the end, there was an underlined, italicized phrase indicating that the provost and deans expect 100% participation in this program. So I learned that a major purpose of awarding endowed chairs is conscription of faculty to become soldiers in the never-ending war on poverty of the CMU endowment—in case any of you are unaware, for an institution of Carnegie Mellon’s stature, the endowment is remarkably small, and I’ll be happy to do my part in trying to build it up.

This is a special year in my career at Carnegie Mellon not only because of the chair but also because in September I turned 64, which means, this is the year during which I can declare my intention to retire soon and, by doing so, receive a large financial incentive bonus from the university. I’m not going to do that, but I am conscious of being a senior citizen, and while I have adjusted very comfortably to often being the oldest person in the room, it has its disadvantages: as a teen-ager I was already an absent- minded professor, and at my advancing age this has become downright dangerous; not too long ago I was at an off-campus meeting and was walking back to my car, deep in thought, got in, and had a moment of panic because the steering wheel was gone and I thought “who would steal a steering wheel?” and then I realized I gotten into the back seat! I sincerely wish I were kidding.OK, so, I’m an absent-minded 64 year-old man, who loves his wife and kids, and you’ve heard some nice things about why I’m being awarded an endowed chair. But this may still leave you with one more question: What took so long?

I’m going to give you two explanations.

First, I’ve always been slow. For one thing, you know that wonderful wife I mentioned, who seems like my perfect match? It took me 38 years to find her!

My academic trajectory was similar. For example, it took me 9 years to publish my PhD thesis, and, this may amaze some of you but, in fact, I was promoted to untenured associate professor with no major publications, so when that happened and I asked my department head, John Lehoczky, for some advice as I looked forward to going up for tenure in the future, he said, “Rob, you were hired, reappointed, and promoted based on an unpublished manuscript. For tenure, you’re going to have to give the senior faculty a break, and get your work into print.” Fortunately, I did that, mostly by admitting that I could use some help, and realizing there was a steady supply of excellent collaborators here at Carnegie Mellon (and then, later, at Pitt as well).

I wanted to tell you that because there’s a moral here.

If I were a different person I might learned things faster, or written out mathematical derivations more efficiently, or discovered at an earlier age how to be goal-oriented in my research, but that just wasn’t part of my mental make-up. I do have an excuse I’d like to try out on you, in the form of one of my favorite quotes, from the late great mathematical statistician David Blackwell (who among other things, received an honorary degree from CMU). He said, “I never wanted to do research, I just wanted to understand. And sometimes, in order to understand, you have to do research.”

Like so many others, I went into academic life because I wanted to understand, and share the understanding, but, also, because the academy would have me: that is, I had a spotty scholastic record, and would have failed miserably at any number of seemingly straightforward, but highly structured, tasks, yet the academy welcomed people like me as long as we demonstrated tenacity to the point of obsession, and some measure of success with things we, and the community, judged worthy of commanding our attention. I’m worried this may be changing. Various forces, including the many pressures we face, and our loss of control over our time, seem to have conspired so that all along the educational process we are relying too much on the easiest ways to evaluate students, and applicants, and we may overlook those who don’t seem to fit some idealized mold. I just hope that my standing here now, with my autobiography, can be a reminder that meritorious contributors to academic life can have a wide variety of profiles.

Now you have to indulge me one more story, which I appropriately kept secret for a long time but recently started telling people, because it illuminates the situation with endowed chairs at CMU, and it provides a second explanation for my getting this chair at an age when I instead could be retiring.

One of the most common reasons people are awarded chairs—and Farnam mentioned this—is as part of a hiring package, or a retention package after they receive an outside job offer. That’s not the case here. However, 10 years ago I had back-to-back opportunities to join statistics departments at universities that were, overall, ranked considerably higher than CMU.

In the first case, I had given a special lecture at this particular university and was ending my visit in the office of the department head when he informed me that he and his faculty wanted to know whether there was anything they could do to get me to join their department.

At first thought, it was tempting. Yet, putting aside any consideration of uprooting the family, and leaving friends, as soon as I asked myself which university provided the better opportunities to pursue my interests, I knew the answer: there was no way I could improve on what I already had. I couldn’t improve my faculty colleagues, who provide the best resource I can imagine in helping me learn new ideas, produce good research, and be involved in creating outstanding educational programs; I couldn’t improve the students; and I certainly couldn’t improve the staff, or the overall working environment; in fact, for someone with my collection of interests, in statistics, machine learning, and neuroscience, with the University of Pittsburgh right next door, Carnegie Mellon was, clearly, the best place I could be. True, during the month of January in Pittsburgh if we could have even a few days when we get see the sun, as my grandmother used to say [Yiddish accent], “Vood be nice,” but you can’t have everything, and there was no way we were leaving, so as soon as I got home I wrote a very polite but firm email, declining to engage in further discussions.

When an almost identical thing happened shortly after, at the other institution, the department head there, seeing my resistance, added “You know, you are actually our second choice for this position; the first person got a chair from their home institution in order to stay there; we could play that game one more time.” The explicitness of the gambit was a new wrinkle, but when I again considered it on my return trip, what came immediately to my mind was that small CMU endowment, and the possibility that this other deep-pocket institution might make me an offer CMU couldn’t match, and maybe CMU wouldn’t come up with that chair, and then what would I do? After all, at CMU there’s a lot of people who deserve chairs but don’t have them (right Farnam?). I couldn’t risk it and, again, I immediately declined.

Many faculty at Carnegie Mellon have stories like these.

For me, it all worked out for the best because now I hold the same chair that Steve Fienberg held previously. This has huge added meaning for me, it’s an additional privilege and honor, because of the many ways that Steve has inspired all of us who’ve worked with him. And also, due to the financial success and generosity of two brothers, Maurice and Leon Falk, the Falk family name is important here in Pittsburgh, especially to those who have been parents, as Loreta and I were, of children who attended the Falk Laboratory school.

I wanted to tell this last story as a way of saying that I’m thrilled to receive the Maurice Falk chair, but at the same time, it doesn’t really add to my already strong sense of pride in being a professor at Carnegie Mellon University: I’m proud to be part of Statistics, Machine Learning, and the CNBC, and to feel that somehow I managed to earn a place in this wonderful academic environment. I don’t know how to characterize what we’re doing right, but I sure hope we keep doing it. And, when the political world is so challenging, here in this relatively young but already great institution of higher learning, it only seems more important that we work hard to do things right.

In our busy work lives, we probably don’t say often enough how much we value each other. So let me go on record: I love you, all. And I’m very grateful that you could share this celebration with me. Thank you all, again, for being here.

Tree of Life Shooting

After the shooting at the Tree Of Life synagogue, on October 27, 2018, many people contacted me, and I sent a series of emails to a wide group of friends and family living outside of Pittsburgh. The last of these, sent 5 days later, had the subject line "Conclusion." The main text of that message appears below. For reference, Jerry Rabinowitz was a beloved physician whom my wife Loreta knew. Joyce Fienberg was the widowed wife of Steve Fienberg, a long-time member of our department and holder of the Maurice Falk chair prior to me. I wasn't especially close to Joyce, but by coincidence I had had lunch with her the day before she was shot to death.

Everyone is trying to “process” what has happened. There is death, and mourning, which would be difficult but, for someone of my age, familiar. And, of course, the deaths were caused by a disturbed individual with an automatic weapon, which is shocking—though not nearly as traumatic as if the victims had been much younger, which they were in other shootings.

Perhaps we are all reacting much like those with some kind of personal connection in other cases, following the all-too-common shooting incidents across the U.S. And, as far as anti-semitism is concerned, that is almost as old as Judaism itself.

But it feels as if there may be something else going on here, as well, an additional irrepressible source of disorientation and fear. I have some thoughts on this. If you have the interest, and the time to go through a long missive, read on.

The services for Jerry Rabinowitz and Joyce Fienberg were wonderful. It is true that I was dreading the pain I would inevitably feel, but it is also true that I have generally found funerals to be uniquely inspiring experiences: in a room full of raw emotion, we are reminded of the most noble and endearing features of a person’s character; and this is especially so when the individual is an unusual, beloved person, as these two happened to have been. Their acts of caring and kindness, recited by family and friends, remind us of our highest aspirations, to behave like them.

The reminder of how we wish to interact with our fellow human beings comes in context. Like so many, I lead my life assuming, with good reason, that the world, over time, tends to get better as long as we do our own little part to push it in that direction. It's not so much to ask, and a funeral serves, in part, to make that simple request.

Given the nature of the crime, the services were, of course, Jewish, and they produced in me a variety of other feelings.

In the first place, many services make me wish I were more religious than I am. I do not mean I wish I followed religious liturgy better (which would be nice, but not worth to me the substantial effort it would take to go from somewhat-informed to expert). Nor do I need a stronger identity, as I feel thoroughly Jewish. And I'm not referring to a set of beliefs: it is easy to confuse religious sentiment with theology, and to presume that words written long ago still carry their original meaning; no Jew I know, including those who are orthodox, believes anything that contradicts modern science. Rather, I wish I could feel religion in my heart more compellingly than I do. Specifically, I wish the prayers, many of which are very familiar, and several of which I like, could reach me not only intellectually but also with the emotional depth that is obvious in regular congregants.

Partly because I feel this subtle disconnect, life-cycle services, including funerals, inevitably make me think about the value of religion, and of Judaism in particular. In the context of this murderous anti-semitic attack, in a synagogue, I have found myself thinking about what it means to be Jewish, and why the presence of Jews is so deeply bothersome to a small but active segment of society.

Anti-semitism is complicated. "Hatred of other” is a piece of it, but there are many other pieces, too, including the occupations Jews have filled successfully in proportions greater than their population prevalence would predict, sometimes far greater. (On the genetics of race, the predisposition of Jews toward many of the things commonly associated with Jewishness, and our need to learn how to talk about this treacherous subject, I would refer you to the cogent discussions by David Reisch.) There is also the Jewish conception of being a “chosen people,” which is subject to interpretation and mis-interpretation; and, of course, there is Israel.

But beyond these most obvious irritants, each of which has its own disputes and subtleties, there is another piece of the puzzle that captures, for me, a deep worry. It comes from the grand master of modern anti-semitism, Adolf Hitler.

What did Judaism synthesize for the world? Many things that were adopted, also, by Christianity and Islam, but one above all: the binding of two otherwise disconnected aspects of human experience, first, the awe and amazement we feel at the natural world and, second, our compelling sense of morality, this pair brought together in a notion of God. My liberal interpretation of the most basic, and arguably most important Jewish prayer (the Shma) has it saying, "To everyone who wonders about the nature of human existence: our duty to try to be good is so crucial, it is as if it is part of the natural world order, which we find so awesome and compelling."

It seems that Hitler may have recognized this. According to the eminent Yale historian Timothy Snyder (NY Review of Books, Sept 24, 2015), Hitler’s fundamental criticism of the Jews was that they introduced the knowledge of good and evil, with humans compelled by God to follow a moral order. Hitler was no intellectual, but he did seem to have a philosophy that accompanied his obsession with race. In a word, it was amoral. He thought the Jews got it wrong, and by extinguishing them, their original sin could be erased.

Squirrel Hill is a major nesting ground for professionals, who value common luxuries, yet it has changed slowly and remains economically diverse. Its stability, and its strong sense of community, come partly from its highly religious population (about 40% are Jewish, the rest are mostly Catholic or Protestant, but also a good share are Muslim or Hindu). The modern trend toward secularism is understandable. Lots of bad things have been done in the name of religion, and religion is not the sole source of either morality or community. But as religion recedes, there is no automatic replacement for it. We have to admit that part of the reason Squirrel Hill feels, to us professionals, like an unusually nice place to live, is derived from the influence of religion.

The attack on Tree of Life was a horrific shooting, and an act of anti-semitism, which took the lives of people we knew. Maybe that's the whole explanation for how we all feel. Beneath these sadly familiar realities, however, there lurks a deeper worry tied up in the incongruity of the attack occurring in Squirrel Hill: is it possible that it was not deranged and "senseless"? What if it would be better understood, like Hitler's doctrine, as fundamentally amoral?

Politics has always been a dirty business, but it has been covered by a useful facade of decorum: facades are the outward appearances we see first. Have we reached a point where outcomes are all that matter?

What science teaches us, above all, is that truth is procedural; the process is what gives us knowledge. Morality, too, is tied to process: we behave well, and society runs smoothly.

Our darkest nightmare from this multiple murder is that it should be considered a consequence of an amoral discourse. We do not know this, but we fear it. Once we lose our sense of process, in science, in law, in journalism, and, most importantly, in the role of morality, we have no guarantee of progress, and no sense of safety.

And what have we done to prevent our decline? Speaking for myself, I have watched, complaining but passive, as the benefits of a good society have become less equally distributed than when I was a child, and affluence has become rarer. In such circumstances, is there really any reason to ask why so many see only outcome, and ignore process? Once we start down that path it becomes self-sustaining, leading to our contemporary crisis. Yes, I know there are many, many aspects of our current situation, many parts of even a partial explanation, and we are stuck mostly with guess-work.

But here's my point: we have our fears that add to our grief. When people we know are killed, and we recognize the amorality of anti-semitism, those fears are hard to shake.